Values, Vision and Principles underlying a Real Circular Economy

You don’t want to put the wagon before the horse. So you need to start with WHY, meaning which values you want to identify with, – and use as your compass in seeking to cause or give rise to change.

Assume you agree with this statement of overall values, vision and principles (cf. this overview) :

A healthy*, fair and environmentally sound economy where cities and communities take responsibility for own supply chains and for reduced inequality, all embodied by the principle of economic democracy.

* Guardian investigation finds 98% of Europeans breathing highly damaging polluted air linked to 400,000 deaths a year. (Matthew Taylor and Pamela Duncan, The Guardian, 20 Sep 2023: Revealed: almost everyone in Europe is breathing toxic air)

With this vision, sustainability, as commonly understood, is no longer enough:

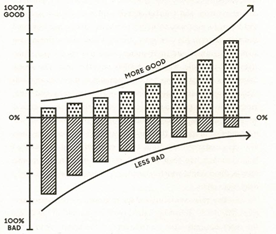

«Sustainability generally strives to reduce impacts on people and the planet as compared to the status quo — say a baseline of previous operations or the industry standard. The ambition for sustainability has grown since 1987, but in too many cases, sustainability is still seen as “doing less bad.”»

Kori Goldberg (February 10, 2023) Back to basics: A systems thinker’s view on circularity

Hardly an inspiring prospect. Michael Braungart puts it in perspective: “If I’d ask you how’s your relationship with your girlfriend, would you answer ‘sustainable’? ” [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_EREVr29wKk]

William McDonough and Michael Braungart follow up in their 2013 book: The Upcycle. Beyond Sustainability-Designing for Abundance [emphasise and text in brackets added] (see also this 2 min. video):

«

Human beings don’t have a pollution problem; they have a design problem. If humans were to devise products, tools, furniture, homes, factories, and cities more intelligently from the start, they wouldn’t even need to think in terms of waste, or contamination, or scarcity. Good design would allow for abundance, endless reuse, and pleasure.

..[in Cradle to cradle we also wrote] about people’s problem of relying only on eco-efficiency to minimize their negative impact. Basically making a suboptimal system more efficient by curtailing how much “bad” it produces: not doing the right things, but doing the wrong things better.

..We like the way businesspeople look at charts: A CEO prefers seeing an upward-climbing line. She wants growth…Much of the well-intentioned environmental work thus far has preferred a different chart, one inclining down toward lower CO2 emissions, decreasing population growth, fewer cubic tons of pollutants ..What if those two charts, of the businessperson and the environmentalist, could be combined? Take a look. The top side of the zero axis is the upcycle—striving to be ‘more good,’ not ‘less bad’..

»

William McDonough and Michael Braungart (2013): The Upcycle. Beyond Sustainability-Designing for Abundance

The goal should not be taken as a general support for economic growth (we have argued in other places for reduced consumption and a slower circular economy). Boullosa refers to McDonough og Braungart who still seems to think that continued growth is defendable, as long as it fills the criteria to be «100% good» [begging the question, with ‘which formula’ does this become a realistic goal?):

“

Why can’t trainers be designed to eventually fertilize your tomatoes, or be reassembled into a new pair of shoes? Eco-effectiveness [as contrasted to eco-efficiency] is defined in [McDonough and Braungart’s] Cradle to Cradle in the following way:

-

- Products should be designed to imitate trees, living things that have perfected the techniques of protection, cooling and regeneration over millions of years: in other words, producing more energy than they consume and purifying the water that they use.

-

- Factories should produce drinking water as a by-product.

Environmental effectiveness targets the source of the problem: instead of reducing energy consumption, it is possible to use the maximum number of resources to create a product or service that avoids pollution, energy use and even is capable of contributing to the environment. To add instead of subtract.

”

Nicolás Boullosa (April 29, 2007) The secret of cradle-to-cradle-ready products. [Emphasise and text in brackets added]

Now, recall this reference from Limitations of the Conventional Circular Economy (CE):

«UN Sustainable Development Goal 8 calls for

-

- improving ‘global resource efficiency’ and

- ‘decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation’.»

By replacing this ‘decoupling’ idea with ‘recoupling of economy and ecology’ promoted by Donough and Michael Braungart, we approach an understanding of a regenerative economy (‘to add instead of subtract’) and thereby also coming closer to a real circular economy. Here we need a full quote from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation to expand on our understanding:

“

Eco-efficiency begins with the assumption of a one-way, linear flow of materials through industrial systems: raw materials are extracted from the environment, transformed into products, and eventually disposed of. In this system, ecoefficient techniques seek only to minimise the volume, velocity, and toxicity of the material flow system, but are incapable of altering its linear progression. Some materials are recycled, but often as an end-of-pipe solution, since these materials are not designed to be recycled. Instead of true recycling, this process is actually downcycling, a downgrade in material quality, which limits usability and maintains the linear, cradle-to-grave dynamic of the material flow system.

In contrast to this approach of minimisation and dematerialisation, the concept of eco-effectiveness proposes the transformation of products and their associated material flows such that they form a supportive relationship with ecological systems and future economic growth. The goal is not to minimise the cradle-to-grave flow of materials, but to generate cyclical, cradle-to-cradle ‘metabolisms’ that enable materials to maintain their status as resources and accumulate intelligence over time (upcycling). This inherently generates a synergistic relationship between ecological and economic systems, a positive recoupling of the relationship between economy and ecology [instead of decoupling].

“

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2013:24): Towards the Circular Economy. Economic and Business Rational For an Accelerated Transition [emphasise and text in brackets added]

Here we also need to highlight McDonough’s take on CO2 greenhouse gas emissions (see more here):

«Carbon is not the enemy. Climate change is the result of breakdowns in the carbon cycle caused by us: it is a design failure. Anthropogenic greenhouse gases in the atmosphere make airborne carbon a material in the wrong place, at the wrong dose and wrong duration. It is we who have made carbon a toxin—like lead in our drinking water. In the right place, carbon is a resource and tool.»

https://mcdonough.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/WAGING-PEACE-BOOK_DIGITAL.pdf

We will come back to this later, suffice to say here, we need to put the carbon back where it belongs: in the soil. How? Part of the answer is to employ farming techniques that through carbon soil sequestration improve long-term fertility and yields:

The capacity for appropriately managed soils to sequester atmospheric carbon is enormous. The world’s soils hold around three times as much carbon as the atmosphere and over four times as much carbon as the vegetation. Soil represents the largest carbon sink over which we have control.

Dr. Christine Jones (2007) Building Soil Carbon with Yearlong Green Farming

This is echoed by new research suggesting that ‘marginal improvements to agricultural soils around the world would store enough carbon to keep the world within 1.5°C of global heating.’ (Fiona Harvey, the Guardian (2023): Improving soil could keep world within 1.5C heating target, research suggests)

McDonough’s ‘Carbon Positive Management Strategy’ also include «..the recycling of carbon into soil nutrients from organic materials, food waste, compostable polymers and sewage.» (William McDonough (2016): Carbon is not the enemy [Published in Nature, November 2016] ).

The takeaway here is that the circular economy is not only about the industrial economy, it also includes the agricultural economy and the interaction between these economies, not least with regard to cities.

Obviously, the above goals cannot be achieved overnight. However, it is important to know what we should aspire to. At the very least, we should try to continuously raise the bar, knowing that there are examples showing that these things are indeed possible.

With this in mind, let’s look at two major principles of the circular economy.

Overall Principles of the Circular Economy

Circular Economy Principle 1: Value Retention

Value retention is seen as the central principle of the circular economy:

«The aim is to safeguard (through design, maintenance, refurbishment, substitution, etc.) the functional and material value of products, components, and commodities for as long as possible.»

[Using the term ‘circularity’, this can be expressed more precisely:]

Circularity is about organising the retention value of both raw and processed materials, components, and products in loops, which leads to an extension of the lifespan, less use of materials, and a lower (environmental) impact. To achieve this requires organising in loops, leading in turn to a fundamentally different economic structure. These profound changes are called a transition.

Jan Jonker, Niels Faber and Timber Haaker (2022) Quick Scan Circular Business Models Inspiration for organising value retention in loops. The Hague: Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy [emphasise and text in brackets added]

Circle Economy Principle 2: Maximum Utilisation of Functionality and Reuse

“Within the circular economy the use of products, materials and resources is increasingly intensified and a strong focus lies on maximum reuse and the retention of the original value of the product or material for as long as possible. Henceforth, the goal is to maximise the utilisation of functionality.”

Making the Principles Operational

Ideally, these principles are made operational within the framework of biological and technical cycles (see graph here) as elaborated upon in McDonough and Braungart’s 2002- book Cradle to Cradle, related to their value statement:

“

What would it mean to be 100 percent good? The cradle to cradle production model mimicks nature as the very concept of waste is eliminated by design; “Materials are designed from the outset so that, after their useful lives, they will provide nourishment for something new.” Either in the form of ‘biological’ or ‘technical nutrients’:

-

- ‘Biological nutrients’ are those that will “easily re-enter the water or soil without depositing synthetic materials and toxins.”

-

- ‘Technical nutrients’ will “continually circulate as pure and valuable materials within closed-loop industrial cycles, rather than being ‘recycled’ –really, downcycled –into low-grade materials and uses.

”

[William McDonough & Michael Braungart (2002: Cradle to cradle. Remaking the Way We Make Things. Emphasise and bullets added] (Related website: https://mbdc.com/)

This does not mean that recycling or other ‘REs’ are disregarded, though. According to the The cradle to cradle product innovation institute:

-

- “We refer to a technical cycle when a product’s materials or parts are reprocessed for a new product use cycle via recycling, repair, refurbishment, remanufacturing or reuse.

-

- Conversely, in the biological cycle, materials or parts are released, and ideally reprocessed via composting, biodegradation, nutrient extraction, or other biological metabolic pathways.”

Building on this is Ellen MacArthur’s butterfly diagram, well explained by the video at this page or at Youtube.

Maximum utilisation of functionality and reuse is facilitated by a range of physical activities that are deployed for the reuse or adaptation of technical materials. To many people, these activities are known as the ‘Re’ or ‘R’ activities. An extensive list of these activities is rendered at the end of this document.

Circularity implies organising in cycles. More precisely, approaching the goal of closing of circles or loops (full closure of circles is difficult for a number of reasons, see separate document). Still:

“Within the circular economy the closing of resource cycles is a key principle. By closing cycles waste can become a resource again and value retention of products and materials can be maximised. Organising in cycles is an immense task in which multiple parties have to cooperate over time to realise value retention and value creation“

Jonker, J., Kothman, I., Faber, N. and Montenegro Navarro, N. (2018). Organising for the Circular Economy. A workbook for developing Circular Business Models. Doetinchem: OCF 2.0 Foundation.

Within this frame, it makes sense to talk about ‘value cycles’, illustrated by the graphs below. Note that behind these illustrations are a variety of business models and strategies, not commented upon here. The importance at this stage is to get a ‘feel’ of the concept of value cycle, bearing in mind that few manage to fully close the cycles/loops.

An important consideration with regard to value cycles is to always ask What’s next? William McDonough explains [Joel Makower interviews William ‘Bill’ McDonough]:

«

When we design what’s next into what’s now, our language changes from “end of life,” which is a human projection, to, say, “end of use.” It changes the nature of the design itself because it becomes design for disassembly. It becomes design for the next new nutrient-management cycle.

So if it’s a writing implement that might be thrown in the trash, like a pen or a pencil, we design it as a biological nutrient. Because if it’s just as easy to go stick it in the ground as a fertilizer spike, it’s a beautiful way to transition from that use period as a writing implement to its next use period — soil nutrition.

Makower: Well, I can see that for a simple thing like a pencil, but with something more complex — a computer or a car or even a multi‑material package — how would the designer and the manufacturer be able to think about what’s next? It’s not even part of the value proposition of what they sell. They’re there to sell cars and not the things after the cars.

McDonough: .. The car is seen as a service that could come apart and the materials could be continuously engaged by the manufacturer. What if you have a car that was essentially glued together, for example, or adhered in a way that it could be disassembled, and the key to taking it apart was actually owned by the company who made the car?

»

Joel Makower (October 22, 2015): Less can be more, but endless is most

With this in mind, let’s look at some illustrations.

Illustration 1: Circularising tires

Source: https://blackbearcarbon.com/

Illustration 2: Logge; Providing customised work in circular office design.

«Logge only uses renewable materials and ultimately wants to bring all products back into the material loop so that there is no more waste.»

Jan Jonker, Niels Faber and Timber Haaker (2022) Quick Scan Circular Business Models Inspiration for organising value retention in loops. Whitepaper, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy, The Netherlands.

Illustration 3 WesterZwam: «Grow oyster mushrooms on coffee grounds. That is what WesterZwam does. On a large scale. But you can do it yourself at home.» Figure text in Dutch only, but see symbols. [follow the link and scroll down to the last infographic for full-size image]

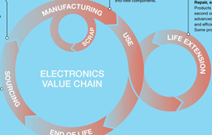

llustration 4: A New Circular Vision for Electronics (scroll down at this linked page to see full-size figure)

![]()

Text references in the figure:

| Manufacturing

Design: Products designed for durability, reuse and safe recycling, substances of concern, substituted out. |

Manufacturing

Re-integration of manufacturing scrap. Scrap metal from manufacturing is reintroduced into new components. |

Life Extension

Repair, Second Life and Durability. Products last longer and have second and third lives aided by advanced refurbishment, repair and efficient secondhand markets. Some products sold as a service. |

Sourcing:

Advanced recycling and recapture. Policies to encourage recycling, and the integration of recycled content into new products. High-tech recycling extracts broad range of materials and keeps them at the highest quality. All e-waste treated by the formal sector.

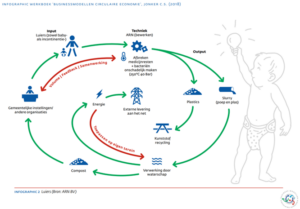

Illustration 5. Arn B.V.: Diapers A cycle/loop image with Dutch text [follow the link and scroll down to infographic no. 6 for full-size image).

Same process illustrated i another figure, but with English text:

Source: https://www.klinger-international.com/en/news/environment-first-unique-diaper-recycling-by-klinger [market/public procurement: private, hospitals, senior homes..] See also https://designawards.core77.com/Service-Design/114386/ReCuring-Diaper-Recycling-System & https://diaperrecyclingeurope.eu/en/homepage/

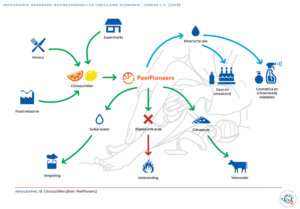

Illustration 6. PeelPioneers extracts the components present in orange peel so that they can then be used as raw materials for making new products. [follow this link and scroll down to infographic no. 22 for a full-size figure]

The raw materials are extracted from the citrus peel in two steps:

- In the first stage, the essential oils that are used in food (for example) are extracted.

- In the second stage, the citrus pulp is retained to be used in animal feed.

Overall Goals for the Circular Economy

- reducing the use of (raw) materials, products and energy*

- value retention of (raw) materials and products

- restoration of the social community #

- increasing soil carbon sequestration

(*) According to the UN resource panel, extraction of raw materials is responsible for half of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions (Ebba Boye [in Norwegian] (Klassekampen 10 juli 2019): Utleie kan bedre forbruk). For Jonker and Faber 2021, the ambition is to “achieve a substantially reduced use of virgin materials: 50% by 2030 and 100% by 2050.” This goal implies a slower circular economy, questioning the economic growth paradigm.

(#) The same authors frame this as «deliberately re-creating the social fabric that underpins inclusivity». For the undersigned, this aligns with the focus on Economic Democracy and reduced inequality (see section D. Why System Change has to include Spreading of Economic Power).

It is also important to think how these goals can complement or even reinforce each other. A case in point is the productive use of agricultural residues where farmers may get economic compensation for 100% of their crops instead of just 20% which is the norm where upto 80% of agricultural residues are burned. According to Paperwise:

«In poorer parts of the world, the agricultural waste is burned in the open air, resulting in valuable resources being lost, unnecessary CO2 emissions, environmental pollution in the soil, and smog as a result of the smoke.

Hundreds of millions of small-scale farmers with very low incomes in developing countries only receive income for the food that the plant produces, which is only 20% of the actual plant.

The European market for paper and board (..) accounts for 20% of the global market. Currently, 50% of paper and board is made from trees from plantation forests, and 50% is made from recycled paper. Each year, the total forested area worldwide decreases by areas equivalent to the size of thousands of football pitches. This is detrimental to biodiversity, CO2 retention, and clean air.

Wood from forests is a primary raw material that takes between 10 and 80 years to grow. Agricultural waste is a secondary raw material that is created within a year. By using agricultural waste as a raw material for paper and board, we obtain food as well as the raw material for paper and board from the same plant and the same piece of land..it gives us the opportunity to create a system in which farmers receive compensation for the food they produce as well as compensation for agricultural waste.»

https://paperwise.eu/en/vision-and-mission/

Note, however, that parts of the agricultural residues may be used for fodder and/or for composting, playing important roles for many farmers. Also for ‘no-till’-farmers the situation may differ. Moreover, conventional composting may be extended through a low cost process of converting agricultural residues to make biochar (with obvious relevance for the issue elaborated upon in the next section).

“[Research] shows that given small financial incentives, small farmers will convert crop waste to biochar, preventing the emission of eCO2, smog precursors, and particulates, and sequestering millions of tons of CO2 annually. This research has huge implications for slowing climate change, improving public health and reducing poverty among the world’s poorest: very small, rural farmers.”

Dr. D. Michael Shafer (2017[?]) Demonstrating Farmer Interest in the Distributed Production of Biochar: Warm Heart Foundation in Mae Chaem. Warm Heart Foundation, A.Phrao, Chiang Mai, Thailand

Increasing soil carbon sequestration

The rational for this was summarised in the first section and related primarily through restoration of soil health in agriculture (carbon farm sequestration). Walter R. Stahel, of many seen as the originator of the circular economy concept, is focusing on the industrial economy only. William McDonough, coauthor of the Cradle to Cradle book (in 2002), on the other hand, is stressing that the circular economy also must include the agricultural sector:

“If you start with soil health, it’s very similar to starting with material health for product. Half of Cradle to Cradle is the biological metabolism which is agriculture [relating to the biological cycle],. The biological nutrient program starts with the soil. So Cradle to Cradle is inherently one half of the program coming from soil as an organism. Soil is at the root of it, so to speak.”

Joel Makower (2014): The McDonough Conversations: Save the soil, save ourselves [Emphasise and text in brackets added]

Accordingly, the restoration of [agricultural] soil health must be seen as part of the biological cycle. And, as already noted (see first section), carbon needs to be put back where it belongs,- in the soil. In fact, carbon is essential for soil health:

“… In healthy ecosystems, when plants convert CO2 into carbon-based sugars — liquid carbon — some flows to shoots, leaves and flowers. The rest nourishes the soil food web, flowing from the roots of plants to communities of soil microbes. In exchange, the microbes share minerals and micronutrients that are essential to plants’ health.

Drawn into the leaves of plants, micronutrients increase the rate of photosynthesis, driving new growth, which yields more liquid carbon for the microbes and more micronutrients for the fungi and the plants. Below ground, liquid carbon moves through the food web, where it is transformed into soil carbon — rich, stable and life-giving. This organic matter also gives soil a sponge-like structure, which improves its fertility and its ability to hold and filter water.

This is how a healthy carbon cycle supports life. This flow kept carbon in the right place in the right concentration, tempered the global climate, fuelled growth and nourished the evolution of human societies for 10,000 years.

Many soil researchers believe it could do so again. Ecologist and soil scientist Christine Jones.. describes the “photosynthetic bridge” between atmospheric carbon and liquid [soil] carbon, and the “microbial bridge” between plants and biologically active, carbon-rich soils as twin cornerstones of landscape health and climate restoration.”

McDonough, W. : Carbon is not the enemy. Nature 539, 349–351 (2016). [Emphasise and text in brackets added]

The above goals should ideally be pursued together. As noted by Jonker and Faber 2021, ‘attempting to reduce the amount of raw materials does not necessarily lead to more inclusion of people..’

Circular Business Models as Vehicles for the Circular Economy

A few quotes will put us on track:

- Business models as key for the circular economy (CE)

«At the heart of the CE is organising the value retention of products, components, and commodities ..in loops. Business models offer a range of (strategic) approaches to give shape to a variety of forms of value retention leading to ample value-creation opportunities. They are therefore a key element in giving operational practicality to the circular economy.»

Jan Jonker, Niels Faber and Timber Haaker (2022) Quick Scan Circular Business Models Inspiration for organising value retention in loops. The Hague: Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy [emphasise added]

- From the single value of finance to multiple value creation

«The concept of value creation is broadened; not only financial value, but particularly ecological and societal value creation are also pursued. We refer to this as multiple value creation. This allows for the emergence of a business model in which several parties create multiple values in dependence.»

Jonker, J., Kothman, I., Faber, N. and Montenegro Navarro, N. (2018). Organising for the Circular Economy. A workbook for developing Circular Business Models. Doetinchem: OCF 2.0 Foundation. [emphasise added]

- From value creation only to the added focus on value retention

«..from primarily financial value creation for individual organisations [and costs externalised to society] in the current, linear economy, to a focus aimed at value retention (of products, (raw) materials) in the form of cycles in the circular economy.»

(ibid.) [emphasise added]

- From transactions of individual organizations to networks and cooperating organizations as the basis for new collective business models

«A decline of the old [linear] economy creates space for the emergence of the new [circular] economy: one that is based on value cycles that are realised over time. The single transaction moment between parties is no longer the central element; instead, we see a chain of interconnected transactions between parties that are realised over time.

This forces one to interact differently as individual organisations are no longer the central element. Instead, networks and clusters of cooperating organisations are the distinctive characteristic of this new economy.

..Value retention as a collective task means that a shift occurs from an organisation-centric perspective to co-creating and co-maintaining a cycle that creates value over time at various moments by re-entering that what already exists ((raw) materials, products) into new transactions. This results in a collective business model, based on a value cycle-centric organisational perspective.»

(ibid.) [emphasise and text in brackets added]

Principles for Collective Business Models and Circular Entrepreneurship

If we accept the premise of collective value creation (see rational in the first section), we also accept the need for collective business models. Jonker, Kothman and Navarro (2018) talks of collective value creation in terms of circular entrepreneurship:

«Circular entrepreneurship.. starts with the search for shared principles which shape the collaboration that emerges when parties try to close a cycle together. Based on these principles, the collective can look for a joint value proposition.»

(ibid.) [emphasise added]

Since the most used template for business models (see next section) is created for the linear economy, we need a new template, fit for the concepts and tools of the circular economy:

«The greatest benefit of a template or a model lies in working with a common language which enables people within and between organizations to communicate unambiguously and work on organizing value creation.»

Jan Jonker , Niels Faber (2021): Organizing for Sustainability. A Guide to Developing New Business Models . Doetinchem: OCF 2.0 Foundation. [emphasise added]

Jonker and Faber 2021 put forward these three principles for value creation in what they call ‘collective and collaborative business models’:

-

- «Collective and Shared Investment: Possibly with hybrid means (time, money, energy, waste, mobility).

-

- Collective and Shared Returns: Sharing in the revenues of the business model (e.g. the electricity generated by an energy cooperative is distributed in proportion to the investment).

-

- Multiple Value Creation: Working simultaneously on tangible and intangible multiple values that are of value to the community or the collective at hand.»

The Business model [is] said to be circular [when]: (not mutually exclusive)

-

- «There is horizontal and vertical chain integration (e.g. the use of one’s own waste in new packaging).

-

- The ambition to organise one or more loops (as a company or in a cluster of companies and organisations and networks).

-

- Strategically the aim is to reduce impact compared to the linear alternatives.

-

- Organising is shaped in such a way as to preserve the value of both raw and processed materials, components, and products and to use them over and over again in multiple loops.

-

- Product-as-a-service [is a business model that enables] various revenue models.»

Jan Jonker, Niels Faber and Timber Haaker (2022) Quick Scan Circular Business Models Inspiration for organising value retention in loops. The Hague: Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy [emphasise and text in brackets added]

Horizontal and vertical integration in the mainstream linear economy:

Horizontal and Vertical Integration approaching a circular economy economy: « [Ikea obtained a] 15 % minority stake in the Dutch plastics recycling company Morssinkhof Rymoplast Group..It was a step towards achieving Ikea’s goal of making its plastic products from 100 percent recycled or recyclable materials by 2020; and it was part of the company’s program to vertically integrate its supply chain. Ikea has also purchased forests in Eastern Europe and a wind farm in Poland to exercise greater control over the supply chain. .. Michelin, one of the world’s largest tire manufacturers, joined the vertical integration game with its acquisition of Lehigh Technologies. Lehigh Technologies is a speciality chemicals company that produces highly engineered, versatile raw materials called micronized rubber powder (MRP) from waste tires. By acquiring a company with an innovative method for recycling tire materials, Michelin is reducing its use of natural resources, in line with its “4R strategy” of Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, and Renew. MRP replaces oil- and rubber-based feedstocks in a wide range of industrial and consumer applications, including high performance tires – Michelin’s core market. Vertical integration helps companies close the loop on their products by giving them greater control over its lifecycle, from beginning to end, and even to rebirth in high value applications. The vertical integration of supply chains is not new, but using it for sustainability purposes is.. Beyond offering manufacturers a secure supply chain, vertical integration of recyclers to both manage end-of-life waste and provide raw materials helps secure demand for recycled materials. One of the biggest challenges for the recycling industry, especially for plastics, is building demand for recycled materials. Vertical integration provides recyclers with a guaranteed customer and in turn ensures stable revenue, allowing them to expand operations and recycle even more waste. In fact, with the added investment from Michelin, Lehigh has been able to expand its circular economy solutions for waste tires globally, in addition to exporting MRP to countries worldwide Lehigh is in the process of building a plant in Navarre, Spain as part of a joint venture with Hera Holdings. » Alan Barton, April 16, 2018, Corporate Citizenship Center: To Go Circular, First Go Vertical (emhasis added) |

A Business Model Template for the Circular Economy

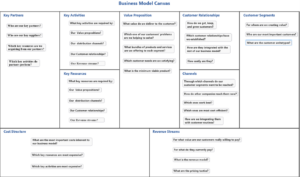

The best known template for business models in the linear economy is the Business Model Canvas (BMC; Osterwalder et al., 2010). It doesn’t fit the bill for collective and circular business models. Still, while our focus will be on Jonker and Faber’s (2021)’s Business Model Template (hereafter BMT), it is advisable also to check on aspects covered by the below BMC.

Text and graphic adapted from Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur (2010): Business Model Generation.

Jonker and Faber 2021 level their criticism of the BMC on three central elements:

-

- “ Logic of value creation: The first element describes the logic of value creation or the value proposition, answering the question What value is created for whom? The implicit outcome of this—certainly with conventional business models—is almost always the dominant pursuit of positive financial results. Although social and environmental values are increasingly important for organizations, these values in the business model rarely receive the attention they deserve.

-

- Organizational model: The second element describes the way in which the value proposition is organized. Most often the point of departure is that this occurs within an organization in collaboration with other parties. But the organization-centred perspective is not the only perspective—this is also possible in loops and networks.

-

- Revenue model: When organizations describe this, a large number of fiscal, accounting, and auditing conventions and rules must be taken into account. This cost–benefit analysis is usually only organization-centred reflecting how the current institutional and fiscal structures work. All kinds of secondary social or ecological effects (both short- and long-term) are excluded from the cost–benefit comparison. In contrast, earning capacity in the BMT refers to creating multiple values, with revenue being one form of value creation.”

Jan Jonker , Niels Faber (2021): Organizing for Sustainability. A Guide to Developing New Business Models [extract only, emphasise and bullets added]

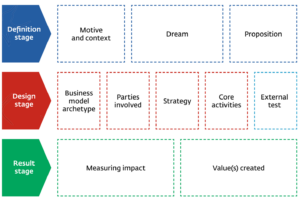

Template for Circular and Collective Business Models

Source: Jan Jonker , Niels Faber (2021): Organizing for Sustainability. A Guide to Developing New Business Models

In the BMT shown above, the Value Proposition of the BMC is termed ‘Proposition’ while the BMC’s ‘Revenue Streams’ is now termed ‘Value(s) created’. And, importantly, Impact is added as a new element, referring to ‘the impact the business model has on ecology and ecosystems, society, inclusivity, and the economy’. Jonker and Faber introduce the BMT as follows:

«The BMT helps enterprising people and their partners to establish a successful and future-proof value proposition that contributes to solving social and ecological issues and results in multiple forms of value creation.»

The biggest invention of this BMT may well be its focus on ‘Business Model Archtypes’ (platform, community-based/collective, and circular business models). These are referred in the undersigned’s course on Cooperative Social Entrepreneurship (see course outline, part 2).